Ok, so we’ve all been nose-deep in the 777s FCOMs recently looking up every little detail on how to fix any little problem that can happen, and hopefully a good number of you have delved deep into our 777 training to learn how these systems work, and extrapolate what to do when something stops working.

Heck, maybe one of you has even tried ditching this plane, despite the finality of your simulation when you touch that water.

However, as some of you may have known and forgotten, total loss of thrust – that’s right, ALL engines going on hiatus – is something that happens despite all the technological advancements of our age.

Plan for Everything … Except Gliding?

4-engine aircraft are statistically never going to have all four engines go mechanical mid-flight, but hey, who remembers (or heard of) British Airways flight 9? Volcanos don’t care much for when your 747 last went through maintenance, or had an engine overhaul. If not for a stroke of luck (Science!), that aircraft would have remained a sizeable glider.

And who can forget the Gimli Glider? Nothing like shorting your fuel by a factor of 2.2. Similarly, Air Transat Flight 236 also leaked its way to empty tanks but glided to a safe landing.

And, of course, the flight that made Capt. Sully famous: US Airways flight 1549, ditching in the Hudson after the engines decided to snack on some (Canadian) geese. These are four success stories, ones that the flight training industry can be proud of, where pilot resourcefulness and skill saved the day.

But What Does This Mean to You?

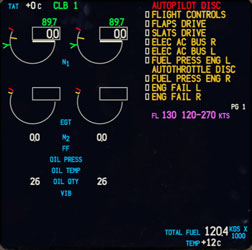

You know what a Ram Air Turbine does. You know the ditching procedure. But when that time comes, will you be able to get it done?

When I was doing my commercial flight training, the bane of my flying existence was gliding. Unlike many of my ex-Air Cadet friends in Canada with glider licences, I never went on that course.

So when it came time for my instructor to cut that engine to idle and say “pick a field”, I always had that feeling in the back of my mind telling me “ok, here we go again… I hope today is a good day”.

And therein lies the problem – I was hoping at the controls of an aircraft. Not flying it skillfully, confident in my ability to put that Cessna down in the field I got to pick myself, but just hoping!

Then the Hardest Landings

It’s called the “PFL”, or Precision Forced Landing. Arguably the hardest maneuver on a Canadian Commercial Flight test, and almost always the final item on the exam as you come home.

It’s called the “PFL”, or Precision Forced Landing. Arguably the hardest maneuver on a Canadian Commercial Flight test, and almost always the final item on the exam as you come home.

Abeam the touchdown markers of the active runway, you cut the throttle, and land right on said markers, regardless of wind conditions. Time and time again I practiced, and it took me a while before I could not only get it within tolerances, but then again to feel like I could get it done first time, every time.

And this got me thinking – I practiced many hours gliding Cessnas onto runways and towards fields, and by the end of it, I felt I could glide that sucker anywhere an emergency forced me to go.

My thoughts continued – why is something like gliding a crippled aircraft matter so much on the commercial flight test, then sort of unceremoniously fizz away from future training? Any IFR pilot knows that to shoot the ILS down to minimums through thick cloud with the wind beating your plane in every direction requires constant practice to maintain that ability, gliding is the same.

So back to what I said earlier:

“Will I be able to get it done?”

Apart from being a very useful question to ask yourself before any flight, especially IFR, I hope this question helps you think a bit about what it takes to put down an aircraft when forward motion is supplied only by proportionate downward motion.

It’s All About Numbers at First

The Air Cadets’ Schweizer 2-33 have a glide ratio of 22:1, so you’ll go 22 feet forward for every 1 foot you go down. Pretty good. I’ve heard the Cessna 172 I glided was 9:1. That’s getting steep. Although I’ve even heard stories of German WWII “gliders” that achieved an impressive 2:1 glide ratio (I’ve managed to find a rock or two with better gliding capabilities than that).

The “rule of thumb” that the internet churns up for commercial airliners is 15:1, which is better than single-engine Cessnas, but worse than actual gliders. And I don’t know the number for the 777, but based on my searches on PMDG’s forum, the fact that people can’t get the 777 to slow down on descent in a reasonable time frame with a standard descent profile leads me to believe it glides well.

Then it’s About Skill

So now you have a rough idea of the numbers behind gliding for a select number of aircraft. But again, these are just numbers. A rule of thumb is good for on-the-fly planning, but I can assure you that when I was at 1000 feet above my touchdown point, I wasn’t whipping out the calculator, nor crunching numbers in my head to figure out how far I’ll be going before I touch down. It comes down to feel, and the ever famous landing “picture”.

Which of you can visualise the descent rate of your aircraft of choice on a particularly “final” approach with no engines, to a field, airfield, or body of water (which is by far the hardest)? And what if you had a 5 knot headwind? 10 knot? 15 knot? With gusts? And I really mean “visualize” through the window and not on your screens or dials, because that ILS we all know and love is quite useless when your plane can’t hold that 3 degree descent.

Learn by Trying (In a Sim)

Well, you won’t know if you can land it until you give it a try, and try it in interesting circumstances. This is why I love my flight simulator – I get to try things! Stick your plane at 38,000 feet above Los Angeles and cut the throttle. Do you think you can glide to, say, Las Vegas?

What about at 3000 feet above touchdown, on approach to your favourite airport? What will you do? Or can you set up a nice ditching scenario and touch down with exactly 0 degrees of bank (remember Ethiopian 961?) You only get a window to look through, so no calculators – let’s face it, all these glide ratios are unofficial.

You’ve done our training, and you know your systems and procedures. Good. Now put that plane on the ground. In that once-in-a-million chance it happens, you’ll be glad you gave it thought.

This article was posted in Basics, Blog, Challenges, Emergency Procedures, Flight Safety, Flightsim Tips, Human Factors, Maneuvers, Real World, Safety

Please note: We reserve the right to delete comments that are snarky, offensive, or off-topic. If in doubt, read the Comments Policy.